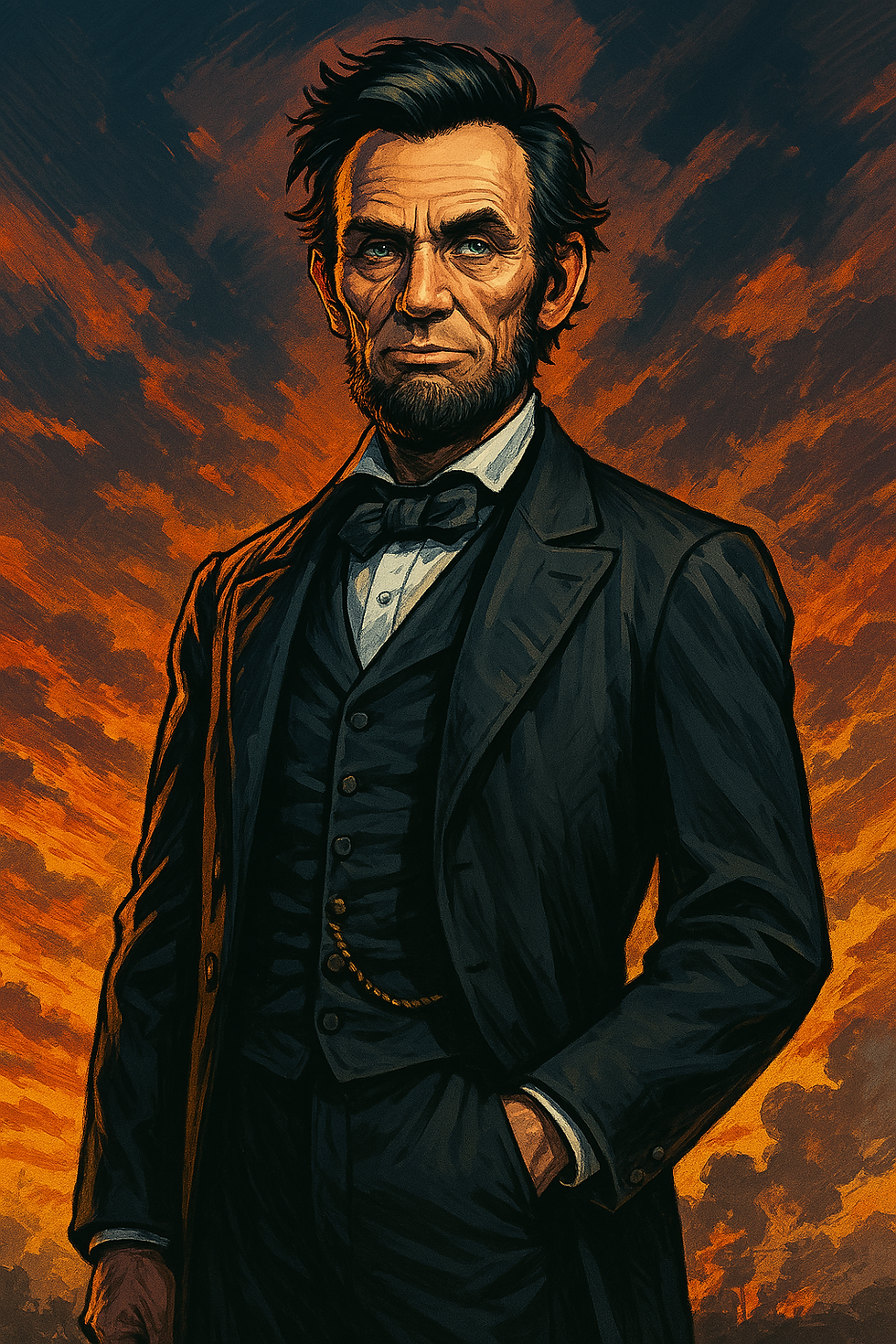

The Heroes and Villians Series - Civil War: Lincoln’s Assassination and the Beginning of a New Presidency

- Historical Conquest Team

- 2 days ago

- 66 min read

The End of the War and the Burden of Peace - Told by President Abraham Lincoln

I remember the moment the news arrived. General Lee had surrendered to General Grant at Appomattox Court House. It was April 9th, 1865. A day carved into my memory—not with celebration, but with solemn relief. The war was over. The cannons had gone silent, and the rivers of blood that had divided brother from brother began to still. I did not cheer, for though the Union had been preserved, the cost was nearly unbearable. Over 600,000 souls had perished. Towns were turned to ash, and families shattered beyond repair. The South lay in ruin, its fields scorched, its cities scarred, and its people—proud and weary—broke in both body and spirit.

The Suffering of the South

For the people of the South, defeat did not merely mean a loss of war—it meant the end of a way of life, a culture they had fiercely clung to, however flawed it may have been. Plantations stood empty or burned. Men returned home maimed or not at all. Mothers and daughters wept for husbands and sons who’d never again walk through the front door. There was starvation in many places, lawlessness in others. The economy had crumbled with the collapse of the Confederacy and the abolition of slavery. For those who had owned slaves, their wealth vanished overnight. And yet, amidst this suffering, there were also the enslaved—now free—walking into an uncertain world with little more than the clothes on their backs, burdened with centuries of oppression and the long road to equality ahead of them.

The Burden of the North

The North, though spared the worst of the physical destruction, did not escape the sorrow. There was not a town, not a city, not a family untouched by grief. I met with mothers who clutched letters stained with tears, widows who wore black for the rest of their days, and children too young to understand why their fathers never returned. The victory felt hollow for many. What good is Union when your heart is heavy with loss? And then there was the question of how to rebuild the South, how to reunite a country where bitterness still festered. I felt it deeply—the wounds were not only of flesh, but of spirit, and healing them would be a task of generations.

A House Still Divided

We had ended slavery in law, but not in sentiment. The prejudices that had fueled secession did not vanish with surrender. Trust had been broken, not just between regions, but between people. Many in the South viewed the North as conquerors, not countrymen. And some in the North saw the South as traitors rather than fellow Americans in need of reconciliation. I feared that if we did not bind up these wounds with compassion, justice, and mercy, we would lose the peace just as we nearly lost the war.

The Human Struggle

I spent many sleepless nights after the war’s end thinking about the emotional toll on the common people. The young soldier who had seen too much. The freedman who did not yet know what freedom meant. The farmer whose sons were buried on battlefields far from home. And those who had given everything for a cause now lost, left only with pride and pain. The war may have ended with surrender, but the human cost continued in silence—in empty chairs, in haunted eyes, in the quiet sobs of the night.

My Hope for Reconciliation

I pleaded for “malice toward none, with charity for all.” I did not wish to punish the South, but to welcome them back as brothers. To those who cried for vengeance, I urged forgiveness. To those who cried for justice, I promised the law would stand for all—Black and white, Northern and Southern. We could not afford to create a peace founded on resentment. Only reconciliation, rooted in empathy, could preserve the Union and give our nation a future.

A Dream Cut Short

I wish I could have lived to see the rebuilding of our land, to guide our country through the stormy waters that still lay ahead. But even in death, I hold hope that the better angels of our nature will prevail. That the wounds will heal. That freedom will blossom even from the ashes. And that one day, North and South alike will remember not the hatred, but the hard-won unity we paid so dearly to preserve.

Vision for Reconstruction and Reconciliation - Told by President Abraham Lincoln

When the guns fell silent at last and the armies laid down their arms, I knew the war was over—but our greatest challenge had just begun. The task before us was not just to rebuild what had been physically destroyed, but to mend the broken bonds of our Union and restore the heart of a wounded nation. I did not desire revenge. I desired reconciliation. I believed firmly that the Union was perpetual, and that our Southern brethren, though led astray, were still Americans. My goal was not to punish them, but to bring them home.

The Ten Percent Plan

Before the war even ended, I laid out what some came to call the Ten Percent Plan. It was simple in design but rooted in mercy. If just ten percent of the voting population in any Confederate state took an oath of loyalty to the United States and accepted the end of slavery, they could begin to form a new government, loyal to the Union. I believed this would encourage a swift return of the Southern states and begin to wash away the bitterness. I sought not to humiliate them, but to extend a hand of fellowship and a chance at redemption.

The Emancipated and the Future

A great part of this vision was the recognition that slavery, that great evil, was no more. The formerly enslaved were now free men and women, and they deserved protection under the law and a real chance to live in freedom. I did not have every answer, but I believed the federal government must play a role in ensuring their rights were secured. Education, fair employment, and citizenship—these were promises our nation had to honor if liberty was to mean anything. I wished to create a peace where freedom truly flourished.

No Room for Malice

There were those in Congress, and many among the people, who cried out for punishment, for the confiscation of lands, and for trials against Southern leaders. But I said in my Second Inaugural Address, “With malice toward none, with charity for all,” and I meant it with all my heart. I knew too well that peace rooted in hatred is no peace at all. If we returned vengeance for rebellion, we would only sow the seeds of future conflict. Our unity must be built on forgiveness and a shared desire to move forward—not backward.

Restoring Government and Trust

To bring the Southern states back into the Union, I wanted to ensure they had functioning governments of their own, chosen by loyal citizens. My hope was that these states would come back not just in name, but in spirit, embracing the ideals of the Constitution, and committing to a nation no longer divided by race or bondage. I would have encouraged a balance—allowing Southern pride to endure in culture, but not in the oppression of others. My belief in democracy guided my hand: the people must have a voice, and the law must protect that voice, regardless of skin color.

A Fragile Dream Interrupted

Alas, my dream was cut short. I had hoped to walk beside my countrymen in the days after the war, to be a steady hand guiding us toward peace. But a bullet silenced me just as the nation began its next chapter. I do not regret what I stood for. My vision for Reconstruction was not perfect, but it was grounded in compassion, in a belief that Americans—North and South, Black and white—could rebuild a nation not as it was, but as it should be.

The Life and Cause of Thaddeus Stevens - Told by Thaddeus Stevens

I was born on April 4, 1792, in Danville, Vermont. My life began in hardship—my father disappeared when I was young, and I was left with a clubfoot, a condition that brought me shame and mockery throughout my life. But adversity does not define a man. It refines him. My mother, a remarkable woman of grit and faith, instilled in me a love of learning and justice. She worked herself to the bone so I could attend Dartmouth College, and though I never completed my degree there, I carried my education and her lessons like armor for the fight ahead.

The Law and My First Battles for Justice

I made my way to Pennsylvania and began practicing law in Gettysburg. There, I quickly earned a reputation as a brilliant, if fiery, attorney—one not afraid to stand against the grain. I took up the cases others would not touch, especially those defending African Americans. The law became my weapon, and justice my cause. In the courtroom, I found my voice. In politics, I would find my battlefield.

The Abolitionist Fire Awakens

I entered public service first through the Pennsylvania state legislature. Early on, I opposed any attempt to restrict the rights of Black Pennsylvanians. I fought a battle in the 1830s against a proposed state constitutional amendment that would have taken away the right of free Black men to vote. I lost that fight. But I remembered. It only sharpened my resolve. Slavery, in my eyes, was not just a political issue—it was a moral abomination. I could not reconcile a nation built on liberty with the reality of men held in chains.

The Rise to National Power

By the 1840s, I found myself in the U.S. House of Representatives, and it was there that my true war began. I became known as one of the fiercest opponents of the slave power. During the Civil War, I threw my full support behind President Lincoln's efforts to preserve the Union, but I urged him constantly to go further, faster. Emancipation was not a political tool—it was a moral necessity. When the time came, I helped draft and push the 13th Amendment through Congress, ensuring the abolition of slavery would be permanent and irrevocable.

Radical Reconstruction and Justice for Freedmen

After the war ended, I saw clearly what others refused to admit: the South was not ready to accept the freedom of Black Americans. I led the Radical Republicans with the firm belief that Reconstruction must be more than rebuilding railroads and plantations—it had to rebuild the very soul of the South. I fought to pass the 14th Amendment, granting citizenship and equal protection under the law. I championed the Reconstruction Acts, placing the South under military supervision until justice and civil rights were truly secured.

My Greatest Hope—and Painful Disappointments

I believed freedmen deserved not only political rights but economic power. I proposed confiscating lands from Confederate leaders and redistributing them to the formerly enslaved. “Forty acres and a mule” was not a slogan to me—it was a foundation for independence. But Congress, and the nation, lacked the courage to follow through. We passed laws, yes. But the heart of Reconstruction required more than law—it required the will to enforce it, and that will began to waver far too soon.

The End of My Days

My health failed me near the end. The burden of war and politics wore down my body, but never my spirit. I died on August 11, 1868. I was buried not in a grand segregated cemetery but in a humble grave in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, one that welcomed all races—because in death, as in life, I refused to be separated by color or caste. My epitaph reads: “I repose in this quiet and secluded spot, not from any natural preference… but, finding other cemeteries limited as to race… I have chosen this that I might illustrate in my death the principles which I advocated through a long life: Equality of Man before his Creator.”

Struggle Within: Tensions Between Radicals and Moderates - Told by Stevens

Though the war had ended in 1865 with the Union preserved, I quickly realized that peace did not mean unity—not even among those who had fought on the same side. Inside Congress itself, our so-called “Union” was split. There were the Radical Republicans, like myself, who believed that the South must be remade—rebuilt not in appearance, but in purpose. Then there were the Moderate Republicans, many of them good men, but too timid in their vision. They longed for a swift reconciliation, for leniency, for compromise. I did not. I had no desire to see the Southern planter class restored to power, nor to see the freedmen abandoned once again to the cruel winds of prejudice.

My Position—Unyielding and Unapologetic

I made my position clear from the first days after Appomattox: the Southern states had committed political suicide when they seceded. They were conquered provinces, and we, the victorious Union, had both the right and the duty to reshape them into free, just societies. To simply allow them to return to the Union as if nothing had happened would be a betrayal of the hundreds of thousands who died, and more so, a betrayal of the millions of newly freed slaves who deserved not just liberty in word, but equality in law and opportunity in fact.

The Clash with President Johnson

President Lincoln had been taken from us—God rest his soul—and into that power vacuum stepped Andrew Johnson. At first, we hoped he might share our determination to punish traitors and uplift the freedmen. But we were quickly disillusioned. Johnson, a Southerner by birth and temperament, declared Reconstruction over before it had even begun. He pardoned former Confederates by the thousands, allowed them to retake political power, and stood by while Southern legislatures passed Black Codes—laws that shackled freedmen in all but name. I was furious. Johnson’s actions spat in the face of justice.

What I Did After the War

I did not sit idle. I used my position as Chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee and as a senior voice in the House to push the Republican Party into action. I called for the impeachment of President Johnson, and though many hesitated, I would not relent. I drafted and pushed forward the Fourteenth Amendment, which granted citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the United States and promised equal protection under the law. This was not a mere piece of legislation—it was a shield for the freedmen, and a sword to cut down the remaining vestiges of slavery.

Reconstruction Acts and Military Rule

When the Southern states continued to resist, and when Johnson tried to obstruct every measure of justice, I helped lead Congress in passing the Reconstruction Acts of 1867. These acts placed the South under military rule, dividing it into five districts governed by Union generals. This was not tyranny, as my opponents claimed—it was necessary oversight. Until the South could demonstrate a willingness to protect Black citizens, it could not be trusted to govern itself. I also fought to ensure that Black men would have the right to vote, and that new Southern governments would be built on the principles of equality—not the old planter aristocracy.

Tensions with the Moderates

Moderates balked at many of these measures. They worried about federal overreach, about alienating white Southern voters, about damaging the Republican Party’s future. I told them the truth: "The future of the nation is not secured by caution, but by courage." I did not come to Washington to preserve injustice under a new name. I came to rebuild a nation that lived up to its founding ideals. That meant confronting uncomfortable truths. That meant changing the very structure of power in the South. And yes, that meant butting heads with those too faint-hearted to finish what we had started.

A Legacy Still in Motion

I knew my time was short—I was aging, and the strain of battle was deep. But I gave every ounce of strength I had to securing a Reconstruction that was bold, just, and uncompromising. Though the Moderates often diluted or delayed our efforts, I never lost hope that we had moved the needle forward. My fight was never just for my time—it was for a future America, where no man would be judged by the color of his skin or the soil of his birth, but by the content of his character and the rights bestowed upon him by God and law alike.

The Long Road After Defeat - Told by President Jefferson Davis

When General Lee surrendered in April 1865, the Confederacy, for all practical purposes, ceased to exist. I was still on the move, unwilling to accept that the cause for which so many had bled and died was truly lost. My cabinet and I retreated southward, hoping to rally what few forces remained. But the truth could no longer be denied: the dream of Southern independence had shattered. On May 10th, near Irwinville, Georgia, Union troops captured me. I was wearing a traveling cloak, not the dress of a woman as many later claimed in mockery. They arrested me as a traitor, and for the first time in years, I had no command, no country, and no hope of victory.

Prisoner of the Union

They imprisoned me at Fort Monroe, Virginia, under harsh conditions. For two years, I was kept in a small, damp cell—my health deteriorating, my dignity battered. They shackled me in chains for a time, a humiliation I bore in silence. I was accused of treason, yet never brought to trial. Some Northern leaders wanted to make an example of me, to hang the President of the Confederacy as a warning to others. But they hesitated—perhaps afraid of what might come to light, or how the South might react to my execution. In 1867, I was granted bail, thanks in part to unlikely supporters, including prominent Northerners like Horace Greeley.

Return to Civilian Life

I was never tried. The government dropped the charges in 1869. My citizenship was never restored during my lifetime. With no home to return to and no nation to lead, I did what many defeated men do—I tried to rebuild a quiet life. My wife, Varina, and I settled in Beauvoir, a home on the Mississippi Gulf Coast. I spent my days reflecting, writing, and receiving visitors—old soldiers, politicians, and Southern sympathizers who still called me “Mr. President.” I never apologized for the war. I believed, until my dying breath, that the South had been within its rights to secede, though I mourned the immense suffering that followed.

A Voice of Memory, Not Power

In the 1880s, I published “The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government,” my account of the conflict and defense of our cause. It was my attempt to set the record straight—not just for my honor, but for the millions who had believed in the South. I did not seek political office again. I knew that chapter was closed. But I became a symbol—for some, a villain of rebellion; for others, a martyr of a lost cause. I never regained the influence I once held, but neither did I fade into complete obscurity.

The Final Years

As the years passed, I watched the South struggle under Reconstruction, rise in resentment, and slowly rebuild under the weight of memory. I saw monuments erected to fallen soldiers, and I knew that while the Confederacy had perished, its story would live on—twisted by some, honored by others. My health failed in the late 1880s. On December 6, 1889, I passed away in New Orleans. Thousands attended my funeral, and I was later reinterred in Richmond, Virginia—the capital of the cause I once led.

Reflection Without Regret

I did not retire in the usual sense, for mine was never a quiet life. Even in peace, I remained at war—with memory, with judgment, with the ever-changing soul of our nation. I did not seek redemption from the North, nor did I expect it. My life was not a life of compromise. It was a life of conviction—right or wrong—and I bore its burdens to the end. History may judge me harshly, but it will not forget me. And perhaps that is all a man like me could ask for.

Whispers Beneath Ashes: Southern Spirit After the Fall - Told by President Davis

After the formal surrender in 1865, a strange hush fell over the South. It was not the peace of healing, but the quiet of shock, humiliation, and grief. Though the Confederate government was dissolved, the spirit of resistance did not vanish with the smoke of our ruined cities. Beneath the surface of the ashes lay a deep, smoldering anger—against the Union, against the devastation, and against the forced changes imposed upon our way of life. Some called it peace, but many in the South saw it as occupation.

A People Defeated, Not Convinced

Let it not be misunderstood—many of our people were exhausted by war. They returned home to scorched fields and broken homes, burying sons and clinging to what little remained. But that did not mean they had forsaken the cause. No, the Southern people had lost the fight, but not the memory. There remained a widespread belief that our struggle had been just, that secession was constitutional, and that the South had fought with honor, if not victory. Confederate sympathies, though no longer openly celebrated, took refuge in the quiet conversations of homes, churches, and country stores.

The Rise of Secret Sentiments

During the early years of Reconstruction, as federal soldiers patrolled Southern towns and military governors oversaw civil order, a new kind of resistance emerged. It was not one of open arms and banners, but of whispers, secrecy, and defiance through other means. Many former Confederate officers and citizens turned to organizing benevolent associations, memorial societies, and Southern heritage groups. Some of these were genuine efforts to honor the dead and rebuild lives. But others became gathering grounds for underground dissent.

The Southern Press and the Pen of Resistance

With the sword laid down, the press became the new battlefield. Southern newspapers, though restricted by Union occupation at first, found ways to voice their frustrations and critique federal policies. Editorials lamented the so-called “tyranny” of the North, the corruption of Reconstruction governments, and the enfranchisement of freedmen. In code and in tone, they kept the flame of Confederate sentiment alive. Letters to the editor, novels, and sermons all served as vessels for carrying the idea that the South had been wronged, not defeated in spirit.

Sympathy from Afar

It would surprise many in the North to know that Confederate sympathizers were not limited to the South. I received letters from individuals in New York, Pennsylvania, and even abroad—men and women who felt the federal government had overreached, or who mourned what they saw as the loss of true states’ rights. Some Northern Democrats viewed Reconstruction as a betrayal of the Constitution, and in hushed tones, they offered support—not for the return of secession, but for a more sympathetic view of the South’s plight.

The Birth of the “Lost Cause”

In these years following the war, a new mythology began to take shape—one I observed and occasionally contributed to. It came to be known as the “Lost Cause,” a narrative that recast the Confederacy not as a rebellion but as a noble stand for constitutional liberty, for tradition, for a way of life unjustly crushed. I saw it as a defense of honor, though others would twist it into something more divisive. Statues were raised, stories rewritten, and the heroes of the Confederacy became martyrs in marble. This, too, was a form of underground resistance—not through violence, but through memory and legacy.

Secret Orders and Dangerous Paths

There were, unfortunately, darker forms of resistance as well. I had no hand in their formation, but I was not blind to their existence. Groups like the Ku Klux Klan arose, claiming to defend Southern values, but their methods were vile—terror, intimidation, and bloodshed against freedmen and Union supporters. These actions did far more harm than good to the Southern cause. They betrayed the principles of honor that our soldiers had carried into battle. While I sympathized with the frustrations of the Southern people, I could never condone such cruelty.

Legacy in the Shadows

In time, the Union government began to soften, and the military presence diminished. But those early years after the war were fraught with tension, unspoken rage, and hidden loyalty to a nation that no longer existed. I became a symbol—silent at times, but never forgotten. The people whispered my name in reverence and defiance, not because they thought the Confederacy would rise again in arms, but because they believed its ideals had not died with Appomattox.

A War Fought Twice—Once with Bullets, Then with Memory

Though I never again held office or command, my presence lingered in these quiet resistances, these post-war murmurings of the South. The war, for many, never truly ended—it simply changed forms. And the tensions between former enemies, and even within the victorious North, would take generations to settle. The Union was preserved. But the peace—that fragile, uneasy peace—would be tested time and time again by the ghosts of a war not easily buried.

Second Inaugural Address: A Call for Healing and Unity - Told by President Lincoln

It was March 4, 1865. The skies above Washington were overcast, as if the heavens themselves shared in the gravity of the moment. I stood once again on the east portico of the Capitol, prepared to take the oath of office for a second term as President of these United States. The crowd before me was quiet—thoughtful. There was no jubilation, no swelling triumph, though victory in the war seemed within reach. The land was weary from years of bloodshed. I did not rise to speak of celebration. I rose to speak of conscience, of mercy, and of our unfinished task as a nation.

Neither Party Expected…

In those brief but weighty minutes, I spoke not as a conqueror, but as a man humbled by suffering and called to healing. I reminded the nation that neither side had anticipated the scale of the conflict. Neither expected the war would last so long, cost so much, or change so many. Yet it had come, and we had endured it—not just as armies, but as a people. And now, the time was near when the guns would fall silent. What would follow would define us more than what had passed.

“Both Read the Same Bible…”

I tried to appeal not to anger, but to shared humanity. I said: “Both read the same Bible, and pray to the same God; and each invokes His aid against the other.” It was not a condemnation of the South, nor a full pardon—it was a recognition that this war was not merely a clash of arms, but a trial of the American soul. I dared to suggest that God had purposes beyond our comprehension, and that the terrible scourge of war was perhaps His judgment for the sin of slavery, visited upon both North and South alike.

With Malice Toward None…

The most remembered words I ever spoke came near the end of that address, not shouted but offered gently, with the weight of conviction:“With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right…”

This was no empty sentiment. It was the very heart of my vision for Reconstruction. I wished not to punish the South, but to bind its wounds, to welcome its people back as brothers, and to ensure that freedom and justice would blossom from the soil once stained with blood.

The Unfinished Work Before Us

I reminded the people that our duty was far from done. The war was ending, but our obligations had just begun. We had to care for the soldiers who had borne the battle, for their widows and orphans, and for the newly freed slaves whose lives and futures hung in the balance. The Union had to be rebuilt—not merely by law, but by compassion. The sins of division could not be washed away by vengeance, only by shared effort and national resolve.

A Message for the Ages

I did not speak long—just over 700 words—but I spoke with every ounce of truth I could summon. That address was my prayer for America—that we might learn from our suffering, humble ourselves before God, and move forward not as enemies, but as one people, committed to justice and peace. I did not live to see the full harvest of those seeds, but I hoped that my words would guide those who came after me. That they would remember: a nation’s greatness lies not in its might, but in its mercy.

And so, on that gray March day, I called my people not to rise up—but to kneel, to forgive, and to build. For in unity, there is hope. And in healing, there is the only victory that truly endures.

The Tragedy of John Wilkes Booth - Told by John Wilkes Booth

I was born on May 10, 1838, in Bel Air, Maryland, into a family where the theater ran thick through our blood. My father, Junius Brutus Booth, was a celebrated actor of English descent, whose name once lit up stages from London to Boston. My elder brother Edwin—well, he would become even more famous. But I was different. Passionate, impulsive, a fire always smoldering inside me. I found the stage young, taking my first roles in Shakespearean drama. Audiences admired my energy, my dramatic flair. By my twenties, I was a rising star on the American stage. Yet behind the curtain, another drama was building inside me—one far more dangerous.

A Nation Fractured

The 1850s turned into a storm of division, and I watched as my beloved South was increasingly demonized. Born in Maryland, a slaveholding border state, I sympathized deeply with the Southern cause. I was not a planter, nor did I own slaves, but I believed fervently in states’ rights, Southern honor, and the idea that the federal government was overreaching. As war broke out, I did not enlist—I was an actor, not a soldier—but I used my fame to support the Confederacy in spirit and in speech. The more I watched Abraham Lincoln rise to power, the more I grew to hate what he represented: a force that, to me, shattered the balance of the Union and crushed the Southern way of life.

Descent into Conspiracy

After the Union’s victory at Gettysburg and the fall of Richmond, I was consumed with despair. Lincoln, I believed, was not just a president—he was a tyrant in a black coat, determined to impose Northern will upon the South by force. I gathered like-minded men—Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt, David Herold—and together we planned what began as a kidnapping plot, a desperate attempt to seize Lincoln and exchange him for Confederate prisoners. But the war ended too swiftly, and our plans unraveled. With Richmond fallen and General Lee surrendered, I grew desperate. Something twisted in me. I thought: if the Confederacy had lost the war, perhaps we could still strike a blow to avenge it.

April 14, 1865

That night at Ford’s Theatre, I stepped onto the stage one last time—not to perform, but to kill. I knew the layout well. I crept into the presidential box during a light moment in the comedy Our American Cousin. I raised my pistol—a .44 caliber Derringer—and fired a single shot into the back of Abraham Lincoln’s head. “Sic semper tyrannis!” I shouted, leaping to the stage, breaking my leg in the fall. But I escaped. I believed I had done something heroic, something that would rattle the world. Instead, I became the most hated man in America.

The Manhunt

I fled into the night, joined by David Herold. For twelve long days, we hid in swamps, barns, and shadows, trying to reach safe haven in the South. But the net was closing fast. The North had erupted in mourning and fury. They called me a coward, a traitor, a madman. I still believed I had done something righteous—something bold. On April 26, 1865, we were found in a tobacco barn near Port Royal, Virginia. Herold surrendered. I refused. The soldiers set the barn aflame. In the chaos, a shot rang out—some say it came from Sergeant Boston Corbett. I was hit in the neck and collapsed, paralyzed. Within hours, I was dead.

Legacy of a Fallen Star

I died at 26, my name forever blackened. The Booth family was shamed. My brother Edwin, who once shared the same blood and stage as I, never forgave me for dragging our legacy into infamy. History remembers me not as the actor I once dreamed to be, but as the assassin of Abraham Lincoln—the man who traded a rising star for a plunge into darkness. I thought I was acting out a tragic finale, that I would be remembered like Brutus striking down Caesar. But instead, I became a cautionary tale of hatred, delusion, and destruction.

Witness to the Words: Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address - Told by John W. Booth

It was March 4, 1865, when I stood among the crowd gathered in Washington City for the second inauguration of Abraham Lincoln. The streets were muddy, the sky gray, and a chill sat in the air—fitting, I thought, for the occasion. I hadn’t come to celebrate. I came to watch, to listen, and to feed the growing storm in my heart. By that time, my hatred for Lincoln had festered into something sharp and dangerous. I had watched this man rise from a frontier lawyer to what I considered a dictator draped in the false cloth of liberty. I stood there not as a citizen, but as a silent judge.

A President on the Steps

Lincoln appeared—tall, gaunt, solemn. There were no trumpets of triumph, no boastful declarations. Instead, he spoke with the weight of a man who had seen too much suffering. But to my ears, there was something infuriating in his tone—righteous, moralizing, cloaked in a preacher’s humility. He wasn’t just claiming the Union’s victory on the battlefield—he was casting it as a divine reckoning. And worse, he suggested that both North and South shared in the guilt, that this war had been the Almighty’s punishment for the sin of slavery.

“Both Read the Same Bible…”

I remember that line. “Both read the same Bible, and pray to the same God…” He dared to say that as if the cause of the South was not righteous, as if our prayers were tainted. To him, the war wasn’t just politics—it was a sacred judgment. And in his soft-spoken way, he pronounced a moral sentence upon us all. I seethed. How dare he compare his crusade to ours? He had unleashed war upon the South—sent his armies to burn our cities, starve our families, and shatter our dignity—and now he dared preach forgiveness?

“With Malice Toward None…”

Then came the words that many remember most: “With malice toward none, with charity for all…” I felt the blood rise in my face. Charity? Had he forgotten the blood-soaked soil of Virginia? The twisted bodies on the fields of Antietam? The flames of Atlanta and Columbia? His so-called charity rang hollow to me. It was easy to offer mercy from a throne built on the graves of Confederate sons. I believed he sought not healing, but submission. He wished to remake the South in his image—and expected us to kneel with thanks.

My Resolve Hardened

As the crowd cheered and applauded, I stood silent and still. I looked at Lincoln not as a leader but as a tyrant masked by grace. In that moment, any shred of doubt I carried about what needed to be done began to dissolve. I had hoped before to capture him—to use him as leverage. But as I listened that day, my heart turned to darker thoughts. I did not see a man seeking peace. I saw a man preparing to crown himself the moral judge of history. And I knew then, deep within me: this man must be stopped.

History Written in Shadows

I left the inauguration with those words echoing in my mind—not as an inspiration, but as a provocation. His call for unity felt like a dagger to the heart of everything I believed in. He stood there, speaking of binding wounds while planting the seeds of domination. What others heard as a sermon of hope, I heard as a funeral for the South. That day, in the shadow of the Capitol dome, I felt the weight of destiny shift, and I made the quiet decision to change the course of it forever.

Not all who heard that speech were moved to reconciliation. I was moved to ruin—mine, his, and a nation's fragile peace.

Confederate Underground and My Descent into the Shadows - Told by John Booth

By 1864, it was becoming clear that the Confederacy—my beloved South—was losing its grip. Atlanta had fallen, Sherman was carving a scar through Georgia, and Lee’s lines were stretched thin. Yet even as the battlefield turned against us, I knew the war was not over in every heart. There were men and women still fighting—not with rifles and cannon, but with ink, whispers, and secret oaths. In Baltimore, in Richmond, even in Washington itself, the Confederate underground network pulsed like a second bloodstream, unnoticed by the Union’s eye. I moved among them—not as an outsider, but as one of their own.

The Web Beneath the Surface

These were not mere rebels. They were doctors, merchants, actors, and clergy. They worked quietly to smuggle intelligence, sabotage supplies, and shelter those hunted by Lincoln’s men. Through secret codes and trusted couriers, I came into contact with operatives of the Confederate Secret Service, some with direct ties to Richmond. I met them in taverns, parlors, and shadowed alleyways. They shared tales of plots brewing—to burn Northern cities, to poison reservoirs, to cripple the Union war machine from within. I admired their nerve. And I began to see myself not just as a witness to history, but a participant—a weapon.

A Plan to Kidnap the President

The idea came slowly, then all at once. In early 1865, I began forming a conspiracy with like-minded Southern sympathizers. At first, it was a kidnapping plot—bold, but not murderous. We would seize Lincoln from one of his public appearances and smuggle him across the Potomac. We believed we could trade him for Confederate prisoners, perhaps shift the tides of war or force favorable terms. I recruited men I believed I could trust: David Herold, Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt, and others. Some were dreamers, others were desperate. I fancied myself their leader—a gentleman saboteur, striking a blow without drawing blood.

The Support in the Shadows

We were not alone. Certain Southern agents and sympathizers provided resources—money, maps, and safe houses. I will not name them, for some were merely patriots who wanted to aid the cause, not sow death. But I knew these networks stretched farther than most dared imagine. Some whispered of help from Canada. Others hinted that men close to the Confederate government encouraged any act that might cripple Lincoln’s administration. Whether or not they blessed my plot, their silence gave me license. In that silence, I heard assent.

The Collapse of the Dream

But the war moved too fast. Richmond fell. Lee surrendered. The Confederacy, as a government, ceased to function. Our plan to kidnap Lincoln now seemed foolish—who would we ransom him to? The prison exchanges had ended, the battle flags lowered. And then came the sight that I will never forget: Lincoln, on the Capitol steps, preaching mercy to the men who had cost hundreds of thousands of lives. “With malice toward none,” he said. To the world, it was noble. To me, it was condescending treason. He was offering peace on his terms, and asking us to thank him for it. I could no longer bear it.

The Turn to Violence

The underground network that once gave me purpose had gone silent. Some fled. Some surrendered. I stood alone in the ruins of failed schemes and shattered dreams. That’s when I made my choice. No longer would I steal Lincoln away. I would silence him. A symbolic act. A final, fiery statement on behalf of a cause that had no more armies but still had voices—mine among them. And though the others hesitated, I pressed forward. Some followed, some faltered. But the plan was mine, and the burden would be as well.

Legacy in the Shadows

When I acted—when I pulled that trigger at Ford’s Theatre—I believed I was finishing what so many in the South had started. That I was the last soldier of the Confederacy, striking at the heart of a government I viewed as tyrannical. I told myself I was not a murderer, but a patriot. But the world did not agree. The Confederate cause would not rise again, and my name became a curse, not a banner. The underground network faded, its fires extinguished by the flood of Union justice.

But in the quiet corners of history, I know the truth. I did not fall alone. I was shaped by whispers, by half-encouragements and secret nods, by men and women who believed the cause still lived in shadows. And it was in those shadows that I lost myself completely.

The Final Days: My First Plan and the Road to Assassination - Told by John Booth

In the final days of March 1865, my mind was ablaze with desperation and purpose. Though the war was all but lost—Lee’s forces waning, Sherman’s path of destruction unchecked—I still clung to the belief that one bold action could revive the Southern cause. But I was not yet resolved to kill Abraham Lincoln. No, at first I aimed to kidnap him. My plan was not murder but leverage. I believed that if we could seize the president, smuggle him into the Confederate lines or into the Deep South, we could trade him for thousands of Confederate prisoners of war and shake the Union’s triumph before it could harden into permanence.

A Conspiracy in Motion

I had my circle—David Herold, Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt, and John Surratt, among others. We met in boardinghouses and backrooms, in the shadows of taverns and rented stables, sketching out routes and gathering intelligence. I had learned that President Lincoln often traveled to his summer cottage, the Soldiers’ Home, with minimal protection. That was to be our moment. I knew the roads, the terrain, and the sympathizers who could hide us on our way South. We would strike swiftly, bind him, and disappear into the night. I rehearsed it a hundred times in my mind.

Why It Failed

But like so many desperate schemes, the timing collapsed under the weight of reality. The president changed his habits. He stopped traveling the route we had scouted. Union patrols increased. Even his movements within Washington became unpredictable. And then came the news that shattered the last thread holding the plan together: Richmond had fallen. The Confederacy no longer had a capital. Lee was retreating westward. Who would we ransom Lincoln to? Who would answer our call with the South in ashes? With every passing day, the purpose of the kidnapping dwindled—until all that remained was rage.

April’s Bitter Light

As the first days of April bled into the middle of the month, I watched the city of Washington erupt into celebration. Crowds filled the streets, waving flags, singing Union songs. They had begun calling Lincoln the savior of the nation. They praised his mercy, his compassion. But I saw something different. I saw a man preparing to welcome the South back in chains, smiling as he paved over the graves of Confederate soldiers. On April 11th, I listened to him give a speech from the White House balcony—speaking of extending the vote to freedmen. That was the moment I turned to a darker path.

The Turn from Capture to Killing

The plan changed—not from failure, but from fury. Kidnapping was no longer enough. I came to believe that Lincoln must die, not for revenge alone, but as a symbolic act—to strike terror into the hearts of the Union, to show them that their war had not ended in peace, but in blood. I would coordinate a multi-pronged attack: Lewis Powell would kill Secretary of State William Seward, George Atzerodt would slay Vice President Andrew Johnson, and I would take Lincoln’s life. In one night, we would decapitate the Union government. It was madness—but I saw it as destiny.

The Calm Before the Bullet

In those last days before April 14th, I moved through Washington like a shadow, performing at the theater, gathering intelligence, sharpening my resolve. I visited the tavern near Ford’s Theatre, paced the alleys behind the president’s box, studied the stage exits. I smiled for the public. I rehearsed my lines. But I was no longer the actor. I was something else now—a man who believed he could change history with a single shot. The kidnapping plan, once bold, now seemed childish. The nation had crowned Lincoln a hero. I would make him a martyr, yes—but not before reminding the world that the South had not surrendered in spirit.

And so I waited. Not for opportunity—but for the moment that felt like fate. And when I learned that Lincoln would attend Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theatre, I knew the curtain was rising—not just on a play, but on my final act.

The Last Evening: My Journey to Ford’s Theatre - Told by President Lincoln

It was April 14th, 1865—Good Friday. The war was all but over, and the burden I had carried for four long years had begun, at last, to lift from my shoulders. Just five days earlier, General Lee had surrendered to General Grant at Appomattox. The Union had been preserved, slavery was being abolished, and the country, though scarred and grieving, could begin to heal. And yet, even in this moment of triumph, I felt no triumph in my heart—only exhaustion, tempered with a deep yearning for peace. The war had aged me beyond my years. I needed, just for one night, to rest my mind.

Why the Theatre?

When the invitation came to attend a comedy at Ford’s Theatre—Our American Cousin—I hesitated. My soul was heavy, my days crowded with meetings, decisions, and letters. But Mary, my dear wife, had grown weary of my constant toil. She needed the lightness of laughter. And truthfully, so did I. The theater had long been a refuge for me—a place where for a few hours, the worries of the nation could fade beneath the hum of dialogue and the rise of music. Despite the warnings from my advisers, who feared it was not safe for a president to move so freely, I chose to go. I believed in showing the people that the Union was whole again, that their president could walk among them, unguarded and unafraid.

The Ride Through the Capital

As our carriage made its way through the streets of Washington that evening, I looked out upon a city rejoicing. Flags waved, children ran barefoot through the spring dusk, and the streets echoed with the sounds of hammers rebuilding what war had broken. It stirred something in me—a hope that our better angels might, at last, prevail. I spoke softly to Mary about our future, about how we might one day return to Springfield, how I longed for simpler things: a quiet home, time with our boys, and a nation no longer at war with itself.

Arriving at Ford’s

We arrived at the theater around 8:30 p.m. The play had already begun. We ascended the steps and were shown to the presidential box draped in patriotic bunting. The crowd stood and applauded. I bowed in quiet thanks, but my mind was far away—still on the families who had lost sons, the freedmen who now stepped into the uncertain light of liberty, and the daunting task of reconstruction ahead. My thoughts swirled as I settled into the seat, the dim light of the theater flickering like a candle in my weary mind.

A Glimpse of Peace

As the play unfolded, I smiled, even chuckled once or twice. The humor was light, and the actors performed well. I held Mary’s hand and whispered something sweet to her—words I hoped would remind her that we had endured much, but the storm had passed. It was a rare and precious moment of peace, a sliver of joy after years of darkness. I did not know it would be my last.

Before the Curtain Fell

Behind us, unbeknownst to any of us, John Wilkes Booth, a man I had seen perform on that very stage, was moving through the darkened passageways of the theater. He was a familiar face to the staff, an actor and celebrity. No one thought to question him as he made his way upstairs with a pistol in his coat and a dagger at his side. I sat unaware, my guard, John Parker, having left his post. The play moved toward its most comedic moment, the audience caught in laughter.

And then, in an instant, the world changed. I had come to the theater to show the country that we were moving forward—that even a president could once again be a man among his people. I did not come in defiance of danger, but in defiance of fear. The war had taken so much. I would not let it take my humanity, nor would I govern as a man caged. I went to Ford’s Theatre that night seeking hope—and left it, not knowing I had given the nation its greatest test of healing yet to come.

Though I did not survive what followed, I pray my final act was not one of tragedy—but a beginning, written in sacrifice, for a future united.

The Day of Reckoning: April 14, 1865 - Told by John Wilkes Booth

The morning of April 14th dawned with a strange brightness—mocking, almost. A calm, golden spring light spilled across the streets of Washington City, as if the heavens rejoiced while my soul churned in unrest. All around me, people were celebrating. The Union had triumphed. General Lee had surrendered just days earlier. The Stars and Stripes fluttered from rooftops, music drifted from saloons, and the Capitol stood draped in triumphant banners. But to me, it felt like funeral colors for a noble republic that had died long ago.

I rose early, restless, and walked the streets with purpose. This day had been brewing in my mind for weeks—some would say months. My earlier plan to kidnap Abraham Lincoln had crumbled under the weight of a crumbling Confederacy. The fall of Richmond, the surrender at Appomattox, and the president’s call for Black suffrage just days earlier had sealed my conviction. The kidnapping had been a dream of leverage; assassination was now an act of vengeance. And I would be the instrument of history.

Finalizing the Plot

The morning hours were consumed with making arrangements. I met with my fellow conspirators at various points around the city. Mary Surratt, the boardinghouse keeper, was told to deliver a message to her Maryland tavern keeper—to prepare arms and supplies for our escape. She did not ask questions. Lewis Powell was readying himself to strike at Secretary of State William Seward. George Atzerodt, ever hesitant, was tasked with killing Vice President Andrew Johnson at the Kirkwood Hotel. Their missions were clear.

I, of course, had chosen the stage—Ford’s Theatre, the place where I had performed and received applause from the very city I now despised. I visited the theater during the day, just as I had done countless times before. The building breathed with life: actors rehearsing, carpenters adjusting sets, and gaslight flickering in the wings. I was a familiar face—no one questioned me. I learned what I had hoped to hear: the President of the United States would attend that evening’s performance of Our American Cousin, along with his wife and guests. I smiled as I left. The stage was set. The actor had written his final scene.

The Calm Before the Storm

That afternoon, I stopped at Peter Taltavull’s Star Saloon, just a short walk from the theatre. I sat quietly at the bar and drank brandy—one glass, then two. I did not tremble. I did not doubt. In my pocket rested the tools of my task: a .44 caliber single-shot Derringer, small and easy to conceal, and a curved dagger, sharpened like my resolve. My horse was waiting in the alley behind the theatre, held by “Peanut” Burroughs, a young stagehand I paid to assist me. I gave him no reason to suspect. I was calm, courteous, even charming. I knew the habits of men like Lincoln—he would arrive late. And he did.

Slipping into the Theatre

The performance had already begun when Lincoln’s carriage arrived. The house was nearly full. I entered the building without obstruction—who would stop John Wilkes Booth, the actor? I passed familiar faces, nodding as I slipped through the lobby and up the narrow staircase leading to the balcony-level corridor. I had prepared the door to the presidential box earlier, drilling a small peephole and carving a wooden bar to wedge the door shut from the inside. It would keep others out, just long enough.

In the hallway behind the box, I paused. No one guarded the entrance. The man assigned—Officer John Parker—had abandoned his post. Whether to drink, wander, or out of carelessness, I do not know. But Providence had cleared my path.

Inside the Box

I opened the door slowly and stepped inside. The president sat forward in his chair, watching the play, his wife Mary at his side. They were flanked by Major Henry Rathbone and his fiancée, Clara Harris. None of them heard me enter. The laughter of the crowd below masked my footsteps. The scene on stage was building to its most comedic line—the perfect moment, loud enough to conceal the shot. I positioned myself behind Lincoln, took out the Derringer, and raised it.

I pulled the trigger. The crack of the pistol was sharp but brief. Lincoln slumped forward in his chair. For a moment, time froze. Major Rathbone sprang to his feet. We struggled—he lunged, I twisted, and I slashed him across the arm with my dagger. Blood spilled. He staggered back. I turned toward the balcony rail and leapt.

The Fall and the Shout

My spur caught on the bunting draped over the front of the box. I fell hard onto the stage, breaking the fibula in my left leg. The pain was white-hot, but I rose—adrenaline surging through me. The crowd, confused at first, now gasped, some screaming, some frozen in shock. I drew myself up as best I could, raised my dagger to the light, and cried out, “Sic semper tyrannis!”—“Thus always to tyrants!” Then, limping, I made my escape across the stage, past stunned actors and fleeing patrons.

The Escape

I darted through the backstage curtain, into the labyrinth of dressing rooms and props. I burst through the rear door, where “Peanut” Burroughs stood wide-eyed beside my horse. He moved to help me mount. I grabbed the reins and, despite the searing pain in my leg, swung myself up and into the saddle. The night air hit my face as I galloped into the shadows of the city. I had done what no other man had dared—I had struck the tyrant, ended the war with blood, not compromise.

As I disappeared into the night, the gaslights of Ford’s Theatre burned behind me, the crowd erupting into confusion and horror. The president of the United States lay dying, and I—John Wilkes Booth—was no longer an actor on the stage, but a player in history, fleeing from the role I had written with my own hand.

My Name is Mary Todd Lincoln - My Night at Ford’s Theatre

I was born in Lexington, Kentucky, on December 13, 1818, into a well-educated and politically connected family. My father was a prosperous merchant and politician, and I was raised in privilege, surrounded by discussions of national affairs and high society. Yet from a young age, I longed for more than the world I knew—for a voice in politics, for a place in history. I was quick-witted, outspoken, and endlessly curious. When I met Abraham Lincoln, a tall, awkward lawyer with sad eyes and a brilliant mind, I knew he was unlike anyone I had ever encountered. We married in 1842, and though our life together was often difficult, I believed in his destiny long before others did.

Our years in the White House were marked by war, grief, and isolation. We buried our son Willie in 1862, a loss that nearly broke me. While the nation tore itself apart, I watched my husband bear the weight of its survival. He had enemies in every direction—critics, generals, political rivals—and I did my best to defend him, even when I was ridiculed. I was accused of extravagance, of being unstable, even of treason because of my Southern roots. But my heart belonged to the Union and to my husband. When victory finally came in April 1865, we thought, for just a moment, that peace had returned. We did not know that death had one more act to play.

The Last Outing

That afternoon, April 14, Abraham told me we should enjoy an evening together. He had been working without rest, and I had begged him for weeks to take a few hours for himself. He agreed, saying with a smile that he longed for “a little relaxation.” We were to see Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theatre, joined by Major Henry Rathbone and Clara Harris. As we dressed that evening, he seemed lighter, relieved. He held my hand as we entered the theatre and took our seats in the presidential box, draped with American flags and lit by warm gaslight. The crowd applauded as we arrived. He bowed gently. The play began.

I remember leaning toward him during the performance, whispering how glad I was that we had come. He smiled and said softly, “Mary, how they laugh.” Those would be the last words I ever heard from his lips.

The Shot and the Silence

Then it happened. A sharp crack tore through the laughter—a gunshot. At first, I thought it might be part of the performance, some terrible joke. But I saw Abraham’s head snap forward, and he slumped in his chair. I screamed his name, reached for him, but he did not answer. Blood soaked the back of his head. My hands trembled as I tried to lift him, call to him, hold him upright. Chaos erupted around us. Major Rathbone struggled with a man—John Wilkes Booth—who then leapt from the box to the stage, yelling something I could not comprehend.

I screamed until my voice broke. “They’ve murdered the president!” I cried. I kept repeating it, over and over. My world collapsed in that instant—not just the loss of a man, but of the soul that had guided a torn nation back toward light.

Crossing the Street

They carried him from the theatre, across the street to the Petersen House. I followed, weeping, my dress stained, my mind shattered. In that dim room, I sat by his side, though the doctors begged me to stay back. I could not leave him. I whispered in his ear, begged him to wake, to speak to me, to see me. But he lay still, eyes closed, breath faint and slowing. I kissed his hand, his face. I called him “my beloved husband.” I was told to be strong—for Robert, for the nation—but how could I?

He lingered through the night, unconscious. At dawn, the room grew quiet. Then the breath left him. He was gone.

The Aftermath of a Widow

I do not remember leaving the Petersen House. I remember only the darkness that followed. My heart was not just broken—it was ripped from me. My grief was met not with comfort, but suspicion. They said I wailed too loud, dressed too fine, spent too much. They did not see the woman who had lost her partner, her home, her purpose.

I would live many more years, but never truly again. I became a widow in a world that did not understand me. I buried another son, Tad, and spent time in Europe to escape the glare of Washington. Eventually, even my own son, Robert, had me institutionalized, believing I was mad. Perhaps I was. But grief like mine does not pass—it lingers, it stains the soul.

My Heart Still Rests With

night in Ford’s Theatre, I lost everything. I lost Abraham—not the president, but the man who held me through heartbreak, who believed in the goodness of people even as they betrayed him. I have been judged by history, perhaps harshly. But I ask only that you remember me not for the rumors or ridicule, but for the truth: I loved him with every fiber of my being. I was Mary Todd Lincoln—his companion, his comfort, and the woman who sat beside him when the light of the Union was stolen away.

My Name is Major Henry Rathbone - In the Box with the President

I was born on July 1, 1837, in Albany, New York, into a well-known and respected family. My father was a prominent businessman, and when he passed, I inherited a substantial fortune that secured me a place in high society. I studied law, but when the war broke out, I chose the sword over the pen. I received a commission as a Union officer and served with distinction in several engagements. War tested my body and mind. I was wounded at Fredericksburg but recovered. Though I survived the war, I would come to learn that peace could offer wounds far deeper.

By the spring of 1865, I was engaged to Clara Harris, the daughter of U.S. Senator Ira Harris, and my soon-to-be stepsister as well. Clara was close to Mary Todd Lincoln, and the president and First Lady invited us to join them for a night at Ford’s Theatre on April 14. It was meant to be a quiet celebration, a small reward for surviving the storm of war. I accepted the invitation with a sense of pride and honor. I had stood on the battlefield for the Union, and now I would sit beside the man who had saved it.

An Evening of Celebration

That night, Washington was still glowing from General Lee’s surrender just five days earlier. The city was alive with bonfires, flags, and music. Inside the theater, the air was light and joyful. We arrived late—just after the play had begun—and the audience rose to applaud the president. He bowed, and we settled into the presidential box, which had been decorated with bunting and a portrait of George Washington.

President Lincoln was in good spirits. He laughed with us during the performance and whispered comments to Mary. He seemed lighter, almost at peace, as if the weight of the war had finally begun to lift from his shoulders. I recall thinking how human he looked in that moment—tall, gentle, tired, but content. I sat beside Clara, who was radiant, smiling at the stage and at the warmth between the Lincolns. It felt like a night meant to mark the end of pain. But fate had written a far crueler ending.

The Shot

It happened during one of the play’s funniest scenes. The audience laughed, the actors delivered their lines, and then, in an instant, the laughter was broken by the crack of a pistol.

I turned toward the sound and saw John Wilkes Booth—a man I recognized by sight—just feet from me, standing behind the president. Smoke drifted from his Derringer. Lincoln slumped forward. Mary screamed. I leapt from my seat, lunging at Booth. We struggled violently. He turned his dagger on me, slashing deep into my chest and left arm. I tried to hold him, but my grip failed. He broke away and jumped over the railing to the stage below, shouting “Sic semper tyrannis!” before disappearing into the wings.

I staggered back, blood gushing from my wounds. Clara shrieked, and I turned to her—her gown soaked in my blood. But all I could see was the president, unmoving, blood seeping from his head. Panic surged through the theater. Screams erupted. Soldiers rushed in. I shouted for help, told them the president had been shot, begged them to bring a doctor.

The Aftermath

Despite my injuries, I helped carry Lincoln across the street to the Petersen House, where he was laid upon a small bed. I remember Clara helping me walk, her hands stained red from trying to stop my bleeding. The doctors did what they could for both of us, but it was clear—Lincoln would not survive.

The rest of the night passed in a haze. I drifted in and out of consciousness as they stitched my wounds. I heard whispers from the next room. I saw Robert Lincoln arrive. I saw Mary’s face, pale and grief-stricken. I wanted to stand, to protect her, to do more—but I was helpless.

At dawn, they said the president was gone. I felt it not only as a citizen, but as a man who had failed in his duty to defend a friend. I had worn a uniform for years, faced bullets, cannon fire, and yet here, in a night of peace, in a place of laughter, I had been too slow to stop a single bullet. That truth would haunt me.

A Mind Forever Marked

Physically, I recovered. Emotionally, I never truly did. The newspapers called me a hero, but I did not feel like one. I had been there, within arm’s reach, and still I could not stop it. Clara tried to comfort me, but she too was changed. We married later that year, but the joy we once shared had been swallowed by that night.

My Name is Dr. Charles Leale - First to Reach Him: My Night with the President

I was born on March 26, 1842, in New York City. From an early age, I was drawn to the sciences and the workings of the human body. Medicine became not only my field of study but my calling. When the Civil War broke out, I left my studies at Bellevue Hospital Medical College and joined the Union Army as a medical officer. The horrors of war were my classroom. I saw young men torn apart by shell and shot, and I worked tirelessly to ease their pain and preserve their lives. In 1865, at just twenty-three years old, I was stationed in Washington, D.C., as a surgeon at the Army General Hospital.

My duties were both grim and routine—treating soldiers, assisting at the hospital, and sometimes attending official functions when time allowed. I had been in the capital only six weeks when I received a ticket to Ford’s Theatre on the evening of April 14, 1865. The war was effectively over, General Lee had surrendered, and the city was alight with joy. I needed a moment away from the wards and deathbeds. That Friday night was to be a brief reprieve. Instead, it became the night I would never escape.

An Evening of Laughter Turned to Horror

I sat just thirty feet from the presidential box. The mood in the theatre was light, the audience swept up in the comedy Our American Cousin. President Lincoln entered after the show had begun, and the audience rose to greet him with warm applause. He bowed modestly, then took his seat. There was no fanfare—just the quiet sense that a great man had come to share in the joy of peace. I watched him for a moment. He looked tired, yet content, as though he had finally glimpsed the peace he had fought so hard to achieve.

Then, in an instant, the laughter stopped. A loud crack echoed through the theatre—a pistol. I saw John Wilkes Booth leap from the presidential box to the stage, a dagger in his hand. He shouted something—“Sic semper tyrannis”—and vanished behind the curtain. I heard screams, confusion, cries of murder. My training took over.

Reaching the Wounded President

I rushed up the stairs toward the box. It was blocked, but I shouted that I was a doctor—the first in the audience to reach the president. When I entered, I saw Mr. Lincoln slumped in his chair, his head bowed slightly forward. His wife, Mary Todd Lincoln, was beside herself, sobbing and screaming for help. Major Rathbone was wounded, and Clara Harris was in shock. But my focus was on the man who had held this Union together.

I found no wound on his chest or abdomen. Then I parted his collar and found a small hole behind his left ear, with signs of bleeding and brain injury. I knew immediately it was a mortal wound. His breathing was shallow, labored. He was unconscious but still alive. With no tools or instruments, I cleared his airway and gave him what support I could. I allowed others to help carry him across the street to the Petersen House, where I continued to monitor him with other physicians.

The Long Vigil

All through the night, we stood by his bedside. We took turns listening to his heart, feeling for any sign of change. He never awoke. Mrs. Lincoln came in and out of the room, clinging to hope, pleading with us. Cabinet members gathered in silence. Secretary Stanton issued orders between clenched teeth. I kept records as best I could, but I also watched—watched the slow, steady fading of a man who had borne a nation’s burden.

As dawn broke, his breathing grew more erratic. At 7:22 a.m. on April 15, Abraham Lincoln exhaled one final time. I placed my fingers against his neck. There was no pulse. I closed his eyes. Silence hung in the air until Stanton spoke the words that still echo through history:“Now he belongs to the ages.”

A Young Man Forever Changed

I was only twenty-three. Just a medical officer hoping for a quiet evening, and instead, I became the first to reach a dying president. For the rest of my life, I would live with the memory of that moment—of his wound, of his stillness, of the sorrow that flooded the capital. I had treated hundreds of soldiers, but no wound felt heavier than that single bullet wound behind the ear of Abraham Lincoln.

Lincoln’s Death and My Reckoning - Told by Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton

It was the night of April 14, 1865. I had only just begun to breathe again. General Lee had surrendered at Appomattox less than a week prior. Washington was glowing with relief and anticipation. After four years of agony, the Union was whole again—at least in name. I had stayed late at the War Department, as I often did. My desk was still cluttered with dispatches, but my mind was already beginning to turn toward the daunting task of rebuilding.

Then the door burst open. A messenger, pale and breathless, delivered the words I feared more than anything: “The President has been shot at Ford’s Theatre.” I dropped everything and ran.

At the Petersen House

By the time I arrived at the small boardinghouse across from the theatre, President Lincoln had already been carried into the back room, laid on a bed too small for his tall frame. He lay diagonally, barely breathing, blood soaking the pillow beneath his head. Doctors moved around him, speaking in hushed tones, but I knew—he would not live to see the sun rise.

The room filled quickly: cabinet members, military officers, close friends, and witnesses. Mary Todd Lincoln came in waves—sobbing, screaming, then collapsing. Robert Lincoln stood still as stone, aged by grief. I stood in the corner, not speaking, not weeping. I watched. I recorded. I took control. Orders were shouted. The telegraph lines burned with my commands. Troops were dispatched. Guards posted. The capital secured.

But no amount of soldiers or steel could stop the tide that had already come.

Watching a Nation Die

I looked at Lincoln—his face pale, still, so different from the man who had paced the halls of the White House with weary grace. I thought of the burden he had carried. The lives he had mourned. The letters he had signed. The mercy he had shown. His enemies had mocked his voice, his walk, his face—but never his heart.

In those hours, I did not think of policy or politics. I thought of his jokes. His quiet nods of approval. His silences, which said more than speeches. We had not always agreed. I was brash, impatient, a man of action. He was slow to move but sure when he did. He knew how to carry a wounded country on his back—and I, for all my strength, could only fortify the weight he bore.

As the night stretched on, his breaths grew further apart. Each one seemed like it might be the last. And then, at 7:22 a.m. on April 15, the room fell silent. The final breath left his lungs. He did not move again.

I found myself standing over him, the room waiting for words. I hadn’t prepared any. I hadn’t thought what one should say when the soul of the nation departs. But the words came as if from someplace deeper than my own voice:“Now he belongs to the ages.” And with those words, Abraham Lincoln became history.

The Weight of What Came Next

There was no time to grieve. I gathered myself and returned to the War Department. The city was stunned. Soldiers lined the streets, citizens fell into silence, others into fury. I launched the greatest manhunt this country had ever seen. Within hours, I had agents across Maryland and Virginia. John Wilkes Booth would not see the same mercy Lincoln had shown his enemies. And he did not.

But even as Booth fled, and justice was prepared, I felt something heavier settling on my shoulders. I knew the man who would now lead us—Andrew Johnson—was not the man Lincoln was. He was stubborn, resentful, a man who had walked alongside Lincoln out of necessity, not shared vision. Would he honor the promise Lincoln made to the freedmen? Would he bind the nation with compassion, or hammer it with wrath? I feared the latter. And I feared the Radical Republicans—men I knew well—would clash with him until the country once again broke into factions.

What He Meant to Me

I had served Lincoln not simply as his Secretary of War, but as a guardian of his will. I had been his sword in wartime. I had been his shield in the shadows. And in his final moments, I had been his witness.

Abraham Lincoln had held this nation together with the strength of his heart. He never sought vengeance, only victory with mercy. He did not ask for worship, only understanding. He bore criticism like armor and met hatred with humility. He had the courage to sign the Emancipation Proclamation, to laugh in times of sorrow, and to forgive even those who would have torn the country in half.

Now, he was gone. And I, Edwin M. Stanton, was left to guard what remained. I would see justice done. I would ensure the traitors paid their price. But I knew, deep down, that we had lost more than a man.

We had lost our compass. And I feared, as I looked out across the Potomac, that the road ahead would be long, bitter, and unsure without him.

The Flight into Darkness: My Escape and Final Hours - Told by John Wilkes Booth

The horse beneath me galloped through the dark alleys of Washington City, hooves striking cobblestone with fury. My left leg throbbed—snapped at the fibula when I hit the stage at Ford’s Theatre—but I gritted my teeth and pressed forward. The city behind me was alive with confusion and terror. Abraham Lincoln had been shot. I had done it. The cry I gave, “Sic semper tyrannis!” still echoed in my ears. I believed, in that moment, I had changed the course of history. My name, I thought, would be remembered as the man who struck down a tyrant, the last bold voice of a silenced Confederacy.

I rode hard through the city, crossing the Navy Yard Bridge after 10:00 p.m.—a feat made possible because I told the sentry I was heading home to Maryland. He let me pass, unaware that he had just waved through the assassin of the president. Minutes later, my co-conspirator David Herold joined me on horseback, having fled from the failed attempt on Secretary of State Seward’s life. Together, we turned our path southward, into Southern Maryland, where Confederate sympathizers were known to live.

Into Hiding: Dr. Mudd’s Farm

Our first goal was survival—my leg needed attention. Before dawn on April 15, we arrived at the home of Dr. Samuel Mudd, a quiet, cautious man and known Southern sympathizer. He took us in, no doubt alarmed at our condition. I told him I had broken my leg falling from my horse. Whether he believed me or not, he set it, bandaged it, and allowed us to rest. It was there, under the low ceilings of his farmhouse, that the reality of what I had done began to settle into my chest.

By the next morning, the entire nation knew. Posters with my name, my likeness, and a massive reward for my capture were being nailed to trees and walls across the region. Dr. Mudd, learning of the assassination, knew now what we had done. He urged us to leave—and we did, quickly and under cover of night.

Through Swamps and Shadows

The next ten days were spent hiding, crawling, and limping through marshes and thickets, making our way deeper into Confederate-friendly country. We were aided by a network of Southern loyalists—silent, brave souls who gave us food, shelter, and information. But the noose was tightening. Union troops, enraged by Lincoln’s death, flooded Maryland and Virginia. The swamps became our refuge and our prison. My leg worsened—infected, swollen, and burning. At times I nearly fainted from pain and exhaustion, but I pressed on, convinced that if I could only reach the Rappahannock River, freedom might be possible.

At Samuel Cox’s farm, we were hidden in a dense thicket known as "the pine thicket" for five days. I lay in the brush, half-mad with fever, eating little, drinking less. The nights were cold, the days damp. But still, I clung to my belief that I had acted for honor. That Lincoln’s death would awaken the South and stall the Northern machine. Each step we took, however, brought no sign of uprising—only silence.

Crossing into Virginia

Finally, with the help of Confederate agents, we reached the Potomac River and crossed it by boat on April 22nd. The water was choppy, and every creak of the oars sounded like a cannon. But we made it to Virginia, my last hope. I thought the people there would rise to protect me—after all, I had acted for them. But the war was over. Lee had surrendered. The fires of rebellion were now only embers. People were afraid. Few helped us openly.

Garrett’s Farm: The Final Refuge

On April 24th, Herold and I arrived at the farm of Richard Henry Garrett, a kind, unsuspecting farmer near Port Royal, Virginia. We told him we were wounded Confederate soldiers. He gave us food, a place to sleep, and a bit of peace. For the first time in nearly two weeks, I rested in a bed—though sleep never came easily.

But the Union’s dragnet had grown massive. Twenty-six cavalrymen from the 16th New York Cavalry, acting on a tip, tracked us to Garrett’s farm. On the night of April 25th, Garrett, suspicious or perhaps fearful, locked me and Herold in his tobacco barn while the soldiers approached. Surrounded, trapped, the final act of my life had begun.

The Flames and the Final Breath

At dawn on April 26th, the soldiers demanded our surrender. Herold gave himself up. I did not. I would not. I stood inside that barn with my pistol drawn, leg throbbing, drenched in sweat, back against the wall. I called out that I would not be taken alive. They lit the barn on fire.

Flames rose around me. Smoke curled through the rafters. I could see the outline of soldiers moving through the haze outside. Then—a crack of a shot. I felt a sharp, searing pain in my neck, and I collapsed. The bullet had shattered my spine. I could not move. I lay in the straw as the fire raged above me.

They dragged me from the barn—burning, paralyzed, barely breathing. I could not speak, but I could still see. The sky above me faded in and out. Someone knelt beside me. A soldier. He said, “He’s paralyzed.” I struggled to speak. Finally, a few words escaped:“Tell my mother… I died for my country.”

The End of the Stage

As the sun rose over Virginia, I died. April 26, 1865. Twenty-six years old. My hands, once used to hold daggers and scripts, now lay still. I had believed I was a martyr, a Southern Brutus striking Caesar for the good of the Republic. But history would see me otherwise. Not as a savior. Not as a hero. But as a murderer, a traitor, an actor who mistook blood for glory.

My Name is Lafayette C. Baker - The Shadow’s Watchman (U.S. Intelligence Chief)